Dorothy Stratton, who had been dean of women at Purdue University before the war, was a member of the first WAVE officer class in August of 1942. A few months later she was asked to head another new women’s military group: the Coast Guard SPARs (from the Coast Guard Motto Semper Paratus, Always Ready).

She said of her appointment to lead the Coast Guard:

I knew nothing about the Coast Guard, nothing. I had never seen a Coast Guard officer. I didn’t know anything. I think I felt if that was the place where I could work, that was fine with me. In other words, I only cared about being where I could feel I was doing something useful, and I thought this was something useful.

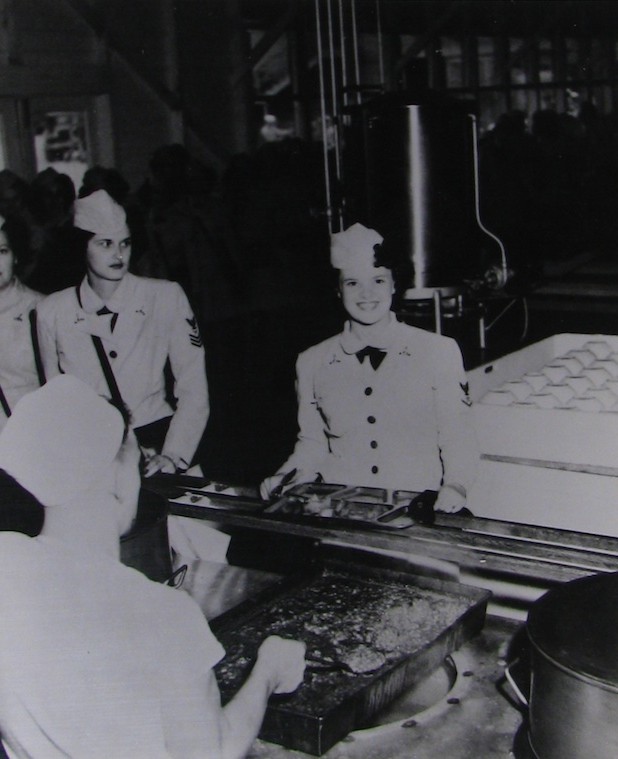

About 12,000 women served in the SPARs during World War II. They were decommissioned at war’s end, and women weren’t allowed to join the Coast Guard again until 1949.

This photograph comes from the National Archives.