A mention of the WAVES wouldn’t be complete with a mention of Margaret Chase Smith. Smith was a Congresswoman during World War II (she would later become a Senator) and has been called by some “the mother of the WAVES.”

It’s a title she disavowed, but she was a strong supporter of women in military service, and was a part of the Congressional committee which expanded duties for WAVES, eventually allowing them to serve overseas. She said later:

I can only say to you that while I knew there was great reluctance and criticism, my feeling has always been that if women were to serve as men, they must accept the responsibilities as well as the privileges. If they needed these women in spots other than those designated by the first law, then there must be very serious consideration given to the legislation for it. I think the women had a great deal to do. They had a great responsibility to uphold the dignity of women.

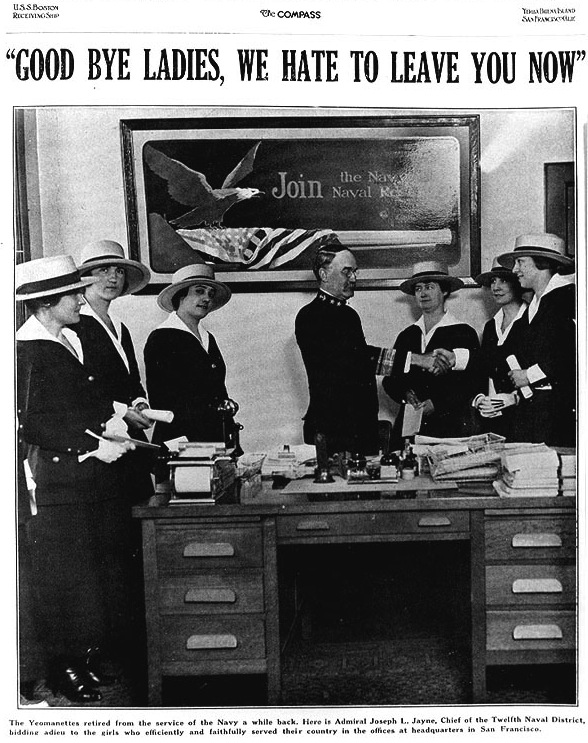

This photograph comes the National Archives.