Jean Byrd Stewart went to boot camp at Hunter College. Just 3 of her class of 1000 women were African American.

After training, Jean was assigned to become a Pharmacist’s Mate, just like half of her class. But she had hoped to do radio work.

I said, “I don’t see any singal, any insignia of radio.” I said, “I’m going ask can I change.” So when I went to ask, who did they send me to but Harriet Pickens. She said, “Well, you know the hospital corps is the area where the Navy women are needed.” She said, “It’s a good field and what you want to do is nice and you do have a background for it. But I think if maybe you had a higher mark, you might have made it, but because of the need for hospital corps.” I don’t know whether I asked her or not, but do you know I had a three-point-nine — now how much higher can you get? But I didn’t say anything, because I knew we were needed and I just left it. And thanked her, and went and that was it.

Jean worked with patients on the hospital ward. Some of the men’s injuries were devastating. She treated men with jaundice. One young man had TB of the spine. Another man had a brain injury and needed to stay quiet because his skull hadn’t healed yet.

He had a friend next door to where he was stationed and he knew it and wanted to see him. At least he was happy he had come this far and wanted to say hello to his friend. And they say, “No, we won’t let you go.” They had to be careful of whoever took him. So while I was duty, I learned about him and him wanting. I couldn’t give him an answer because I wasn’t in the position. But one day he wasn’t there. And what had he done? He had gone next door to visit his friend. He was so happy he knew what to do. When he finished he came back. He knew where he was, where he had come from and where he had to go. And he came back and he was happy and contented. And what could you do? You didn’t want to smile and yet you were happy for him because — that was something. That was something.

Jean left the Navy in May of 1946.

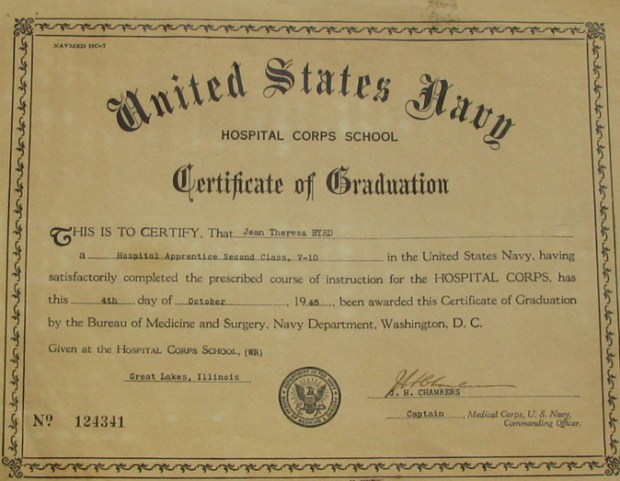

This is a copy of Jean’s graduation from the Hospital Corps school in Chicago, Illinois. It comes from the collection of Jean Byrd Stewart.