Continuing our theme of Asian-Pacific Heritage month, we’re going to begin a series looking at the WAVES’ experience in Hawaii.

Initially, the WAVES were only allowed to serve stateside, but by late 1944 discussions began to expand their duties to overseas. And that included the then-US territory of Hawaii.

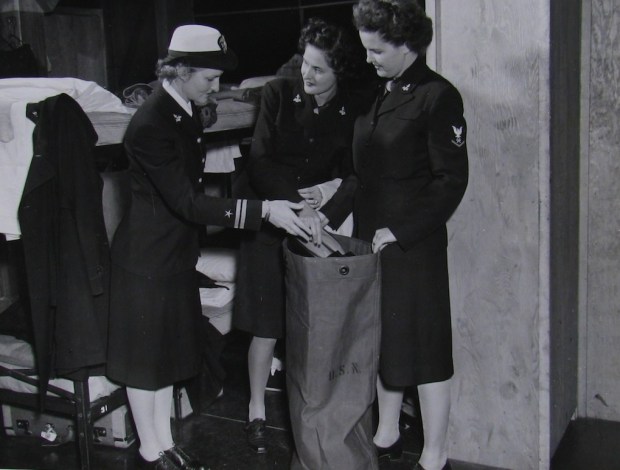

This image shows the first members of the Women’s Reserve of the Navy and Marine Corps doing a preliminary survey of the area in October of 1944 before sending female personnel.

The people shown are (from left): Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghermlevy, Colonel Ruth Street, Lieutenant Commander Jean T. Palmer, Major Marian B. Drydenyof, Vice Admiral John H. Towers, Lieutenant Commander Joy Bright Hancock, and Brigadier General L.W.T. Weller Jr. It comes from the National Archives.