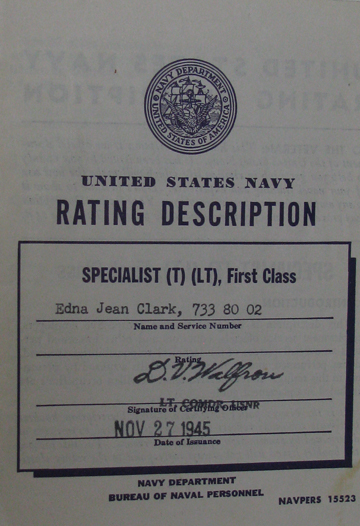

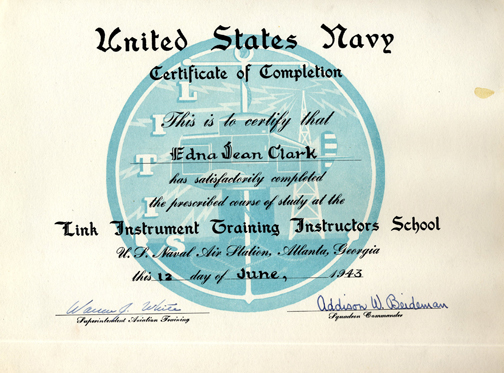

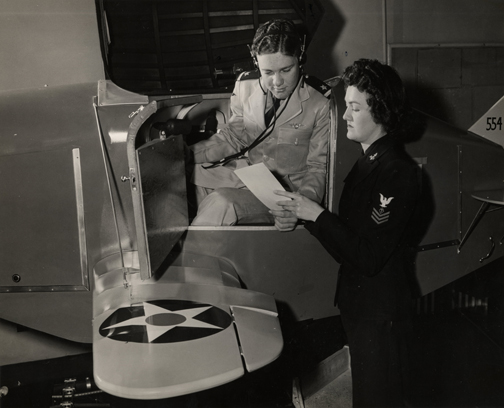

WAVES typically didn’t get flight pay, or extra money for serving aboard an aircraft. But Jean Clark did receive some extra training so that she could get the flight pay, as seen in this copy of her certification.

The officer at Lake Washington NAS thought that Jean deserved the extra money. But that meant that she had to fly sometimes. One flight was particularly memorable:

One time he said, “We’re going out. You might want to go.” I said, “OK.” We’re going to deliver a captain to a flatop. That means we’re taking the captain back to the aircraft carrier. He says, “They’re out there off the coast,” he said, but he says, “It’s top secret. So you have to keep still about it.” So we took the captain out to the carrier. Off the coast of Seattle. It was a rough rough sea. The waves were coming in like crazy. You might think that landing on water is a soft landing? It’s like landing on a pile of rocks if you hit water. And it’s bumpy. So we hit down and they put down a small boat from the aircraft carrier to come out and get the captain. They captain came out on the pontoon of the little widgen waiting to get picked off as they came by. They made several swipes. The commander says to me, “You know, they better get him pretty soon. Those waves are getting pretty high. We may not get out of here.” I thought “Oop, well, this is it.” It did look pretty dangerous. Pretty soon, they did grab him and get him off and take him back. The commander says, “Hold on!” And here was this big wave coming towards us. I mean, big. So he, I could see us heading right into that wave, and we went right into it and right through it and on and we’re airborne. He says, “Well! We made it!” (laughs) That was the most exciting thing that happened to me when I was in the Navy.

The certification comes from the collection of Jean Clark.