Here are some interesting facts and figures about public sacrifice during World War II:

1. The tax rate for most Americans averaged about 20%. For the richest Americans, the tax rate ranged between 80 and 94%. The government framed taxes as a patriotic duty so that the county could pay for a war on multiple fronts (Europe, Africa, The Pacific) and end that war quickly. American involvement in World War II lasted from December 1942 through August of 1945; the last troops were demobilized by 1946.

1. The tax rate for most Americans averaged about 20%. For the richest Americans, the tax rate ranged between 80 and 94%. The government framed taxes as a patriotic duty so that the county could pay for a war on multiple fronts (Europe, Africa, The Pacific) and end that war quickly. American involvement in World War II lasted from December 1942 through August of 1945; the last troops were demobilized by 1946.

2. People were asked to change their eating habits in order to help preserve more essential food for American troops. Things like sugar, butter and meat were all in short supply to the average public. People received ration coupons, which they used when purchasing items.

3. And it wasn’t just eating, People were also limited as to the amount of gasoline they could purchase. By the end of 1942, more than half of the vehicles in the country were limited to just four gallons of fuel a week (cars on average got about 15 MPG). War workers and other “essential” personnel could get more gasoline, but the vast majority of the public was limited in terms of personal driving.

4. Other industrial goods were also rationed. Tires were the first, because most rubber came from the Dutch East Indies, which was controlled by Japan. But steel was also crucial to the war effort. Consumer car production during the war was suspended. Manufacturers looked for alternate ways to package caned food goods.

5. People coped. Magazines discussed ways to use soy and other non-traditional products as meat and sugar substitutes. People planted Victory Gardens, backyard or neighborhood gardens where they could get unlimited amounts of vegetables for the dinner table.

6. Since people couldn’t drive, they turned to mass transportation, which was provided by both cities and towns as well as private companies. Buses served communities large and small across the country, offering a way to get from one place to another. Train service was also more extensive. Americans used mass transit in record numbers, hitting a peak of 23.4 billion riders in 1946. Carpooling was also encouraged.

7. There were other government-mandated restrictions. The government Office of Price Administration froze prices on many raw manufacturing materials in order to stave off inflation which is often common during the war. Women’s hemlines were raised so as to save fabric. People living near the coasts used blackout curtains to keep the cities dark in case of an attack.

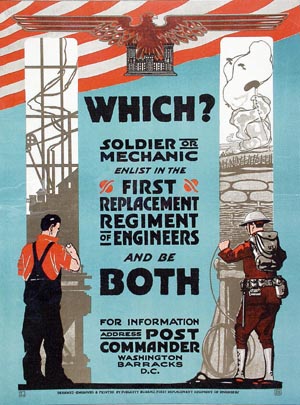

8. Men between 18 and 64 had to register for the military draft, and men between 18 and 45 were immediately eligible for induction. Draftees would serve in the U.S. Army and Marine Corps. But people also enlisted for the various services (the Navy was an all-volunteer branch), largely to be in control of their own destinies. About 12 million people were serving in the U.S. military at its peak strength in 1945.

8. Men between 18 and 64 had to register for the military draft, and men between 18 and 45 were immediately eligible for induction. Draftees would serve in the U.S. Army and Marine Corps. But people also enlisted for the various services (the Navy was an all-volunteer branch), largely to be in control of their own destinies. About 12 million people were serving in the U.S. military at its peak strength in 1945.

9. Unlike the Depression, when the unemployment rate was around 20%, people were working during World War II. The unemployment rate was less that 2% for most of the war. Stateside people were employed by the military and other government agencies or worked in war production plants (in addition to other businesses, shops, schools, etc., which remained open during the war). People had a pent up urge to spend the money they made.

10. So, the government asked people to buy War Bonds, essentially helping to financially support the war OVER AND ABOVE the taxes they paid. Bonds matured in 10 years and sold at 75% of their value. Bond sales totaled $185.7 BILLION during the war, and more than 85 million Americans — half the population — purchased them.

(Courtesy of historyiscentral.org)

(Courtesy of historyiscentral.org)